Last Autumn, our founder Florence Gaudry-Perkins had the opportunity to participate in a roundtable organized by the association ‘Femmes Pharma’, which supports women’s professional development in the healthcare sector. The theme of the roundtable was "The impact of digital health and the role of women".

Now more than ever, as digital health is experiencing unprecedented growth due to the pandemic, the question of the place of women in this field deserves attention. Franck Le Meur, CEO of TechToMed, moderated the discussion with four women from different backgrounds: Laurence Comte-Arassus, General Manager GE Healthcare France, Belgium, Luxembourg and French-speaking Africa (FBFA); Virginie Lleu, Founder and Managing Director of L3S Partnership; Laura Létourneau, Ministerial Delegate for Digital Health; and Florence Gaudry-Perkins, Founder and CEO of Digital Health Partnerships.

Digital health in the Covid era: unprecedented growth, new challenges

The phenomenal impact that the pandemic has had in the field of digital health was first discussed. As noted by Laurence Comte-Arassus, digital health now encompasses all age groups and populations. Global digital health investments doubled between 2019 and 2020, from $10.6 billion in 2019 to $21.6 billion in 2020. The use of digital health services exploded around the world, particularly in the field of telemedicine. In 2020 the use of digital services has, for example, not only increased in the UK (+912% of teleconsultations according to the NHS), but also in India (+500% of teleconsultations between March and May 2020), the United States (+2,000% of teleconsultations at Amwell between January and March 2020), China (+900% of Ping An Good Doctor uses in January 2020), and in many European countries. In France, Laura Létourneau explained, there has been a real shift to teleconsultation: remote consultations increased threefold among patients and fivefold among doctors, with an 80% satisfaction rate on both sides. These fundamental trends are now leading to the emergence of new professions specializing in both digital and healthcare, added Virginie Lleu.

Despite the urgency of the pandemic situation, only certain countries put in place adequate regulations to cope with the demand generated by the crisis. Even countries advanced in digital innovations have not necessarily created arrangements to reimburse telemedicine services. This is not the case for France, which can be set as an international example given two impressive investment plans contributing to the development of digital health: The Ségur numérique, a €2 billion plan for the construction of a public digital health platform, and the deployment of France Relance, which allocates €600 million for the training of health professionals, research and development, testing sites, etc.

Nevertheless, as we reach a decisive turning point in this field, some efforts remain to be made so France can involve itself in decisions being made at the international level (data exchange between countries, interoperability, etc.). In recent years, many global governance bodies have been set up in which France’s presence is largely absent. France’s presence on the international stage is not only warranted, but above all politically and economically strategic: it is in France’s interest to be immediately involved in discussions regarding the frameworks, rules, and standards that will define the global exchange of health data. This is the topic of a policy brief we recently wrote with the think tank Santé Mondiale 2030. Laura Létourneau explained that the Ministry’s international teams are being strengthened and that the French Presidency of the European Union (which began in January 2022) presents a great opportunity. However, France can go further by joining groups such as I-DAIR or Transform Health.

On the African continent, which Digital Health Partnerships substantially collaborates with, some countries are emerging as forerunners: Rwanda, a true land of innovation, has been putting in place an enabling framework to foster and encourage the acceleration of digital health for many years. Before France invested in a national digital health strategy, we had no hesitation to say that Rwanda was already ahead of the curve. For example, Rwanda permitted an American company that delivers blood bags by drone to develop locally, even though it was encountering hesitancy and regulatory barriers across the Atlantic. It is interesting to observe what is happening in countries such as Rwanda and to draw inspiration from them for the implementation of innovations in so-called "developed" countries (this is the concept of "reverse innovation"). At the national level, countries should also establish joint governance between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Telecommunications (such as is the case in Rwanda): this was one of the recommendations in the 2017 report of the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, which stressed the importance of inter-ministerial cooperation but also the leadership of politicians, which is fundamental for this field.

Women in digital health: what role, what place?

While women’s place in digital health is still in its infancy, there are many glimmers of hope. In the healthcare sector, more women work in digital roles in Big Pharma companies than ever before, said Virginie Lleu. However, globally, it is noted that while 70% of healthcare providers are women, only 5% of them hold leadership positions! According to a 2020 Rocket Health report, only 40% of female founders of digital health companies said they raised required funds compared to 62% of men. There is some way to go, although there are great examples of women entrepreneurs in digital health to highlight, including those from Africa, e.g., Nneka Mobisson, founder of mDoc in Nigeria, and Juliana Rotich in Kenya, who created Ushahidi.

During the roundtable, efforts to diversify hires within respective organizations were highlighted – this is positive news! Each guest made a point of encouraging women to get involved in the digital health field. In the eyes of participants, women don’t need to copy the mindset of men to stand out and succeed, quite the opposite. The new generation of women entering digital health are supportive and ready to engage, and the health sector has a strong obligation to commit to women’s leadership development! Digital health contributes to increasing access to healthcare and to the reduction of inequalities. At Digital Health Partnerships, this is our raison d’être. We are committed to working with countries that lack the health infrastructure and health workforce required to improve access to care. Remember in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, there are roughly 2 doctors for every 10,000 people, compared to 49 in the European Union.

Our thanks to Femmes Pharma, Women in Tech, Digital Ladies and Techto Med for organizing this exciting roundtable, to the panelists and to Franck Le Meur for the rich and stimulating exchanges.

In lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs), access to health remains an important issue to solve.

Shortage of healthworkers is one challenge among others: according to the World Bank, there is only 1.2 doctor in LMICs (versus 2.9 in high income countries) and 2.1 nurses or midwives per 1,000 people (versus 8.7 in high income countries). At the same time, 90% of smartphones users will be located in LMICs in 2020. The promise of digital health to address some of the underlying health systems challenges is undeniable. Digital health can significantly support the achievement of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), one of the targets of the third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). A recent report estimated for example that 1.6 billion people could benefit from quality medical services through digital health solutions. Beyond access, digital health can also play an important role in terms of cost reduction and health systems efficiency and quality. Although not many countries have yet analysed the impact of digital health on their systems, it is notable that Canada estimated that their investments in digital health (implementation of electronic medical records (EMR), telehealth and district information systems) generated savings of CAN$16 billion since 2007.

Many challenges remain to fully leverage the tool of digital health. Fragmentation, data interoperability and lack of appropriate legislation and laws are still prevalent. The Ebola crisis was one of the wake-up calls to the growing realisation that data fragmentation needs to be addressed if ICT tools are to be used for effective data collection and analytics. Data needs to be integrated to make it useful in real-time to healthcare professionals or public health authorities.

A striking example of what we mean by fragmentation is Mali where there are 11 different mobile health initiatives for maternal and child health funded by different institutions. Moreover, most of these institutions use their own tools and systems which are not interoperable with systems used by the national eHealth agency. In LMICs, the number of digital health projects had increased by more than 30% between 2005 and 2011 but two thirds were still in pilot or informal stages. Although this statistic is a bit dated, “pilotitis” has been a common word used in the field of digital health for many years and is still prevalent.

Many countries still do not have the appropriate data security and data privacy regulations in place and this is a current hot topic that hinders the trust of any user. A lack of proper legislation to govern mHealth Apps or connected devices and sensors can also undermine investments in countries.

Beyond these obstacles, other barriers still need to be tackled: insufficient human and technical capacity to analyse health data and meet patients’ needs, resistance to technology, unsustainable financing, lack of coordination between national ICT plans and national digital health strategies, connectivity gaps, quality and performance issues of networks, and lack of reimbursement schemes.

As the cycle of digital health evolves, there is a growing realisation on the fundamental role governments have to play in advancing the use of technology for health by developing the right policies and infrastructure as well as building capacity for digital health. In February 2017, the Broadband Commission Digital Health Working Group (co-chaired by Novartis Foundation and Nokia) published a report called: “Digital Health: A Call for Government Leadership and Cooperation between ICT and Health”. It advocates for governments to take action on national digital health strategies to solve the fragmentation dilemma and help tackle the challenges mentioned above.

As of 2016, 58% of WHO’s member states had developed national digital health strategies. This does not translate in the fact that countries have implemented these and there is therefore still a lot of work ahead. Implementing a strategy is no minor task and represents a significant investment: the Government of Rwanda committed US$32 million for its first 5-year eHealth plan for example. Tanzania’s more recent digital health road map calls for overall investment of approximately $74 million. The above-mentioned report looked into 8 countries that managed to advance effectively the digital health agenda (Canada, Estonia, Malaysia, Mali, Nigeria, Norway, the Philippines and Rwanda) and provides key insights and lessons which other countries can leverage from.

A key finding was that countries achieving success in implementing strategies shared responsibility and investment between the Health and the ICT authorities (typically between Ministry of Health, Ministry of Communication and the eGovernment agency).

Perhaps the most important learning from the global scan that was done, is the utmost importance of having the appropriate leadership and governance in place to enable the effective implementation of a national digital health strategy. Many stakeholders saw this as the most challenging first brick to attain in order to robustly build around the other essential components of a strategy: Strategy & Investment, Standards and Interoperability, Infrastructure, Legislation & Policy & Workforce. Government leadership is vital in fostering an enabling environment for digital health policies and an effective cross-sectorial governance mechanism, the basis for facilitating alignment and cooperation between health and ICT sectors.

In terms of governance and government leadership, some LMICs are true models. In the Philippines, close cooperation between health and ICT ministries has been materialised in a joint MoU and governance mechanisms with clear role and responsibilities, and Rwanda’s very strong high-level commitment of broadband policies and extraordinary intersectoral governance makes it a real example for many countries around the world. It embodies the promise for these countries to leapfrog and avoid the difficulties today faced by high-income countries, often linked to legacy infrastructure and systems.

The digital health ecosystem in LMICs is entering a new phase where the focus is starting to shift to investing in “the roads” for digital applications and services to scale. In other words, a shift to a “system” thinking vs. solutions. This evolution will accelerate the scaling and development of digital health and help in achieving Universal Health Coverage.

It was so exciting to be part of the important place digital health took in May at the Transform Africa Summit in Kigali, the leading African forum organized by Smart Africa bringing together global and regional leaders from governments, business and international organizations to collaborate on new ways of shaping, accelerating and sustaining Africa’s ongoing digital revolution. With over 4,000 attendees and 90 countries represented, the fact that the Digital Health Hub comprised no less than 5 very interesting sessions and panels in the forum was a significant step in the ecosystem realizing the importance of this theme to achieve a fully digitalized Africa. I am also very grateful to the Novartis Foundation for its sponsorship in making this event happen, thereby underlining again their leadership in this space on the continent. The teamwork between the Smart Africa team, WHO and ITU was gratifying and showed the power of collective impact in bringing together some great content and speakers.

The 80.8% mobile penetration and 25.1% Internet users' penetration, against 99.7% and 47.1% at the world level (ITU source 2016) has already allowed digital health in the African Region to contribute to strengthening health systems and accelerating the attainment of the SDGs, including UHC. In the African region, 26 countries have national digital health strategies. There is no question that with the predicted exponential increase of internet usage (+20% since 2017 according to ‘Digital in 2018’ report) as well as smartphone penetration, the potential of digital health in Africa will keep growing.

I was thrilled to moderate the session entitled “Government Leadership in Digital Health-Breaking Silos and Mitigating Pilotitis”. Government leadership for digital health has become increasingly important as there is a great need to build core systems and platforms as well as create harmonization in what is still a fragmented space. The Digital Health Working Group from the Broadband Commission released last year a report entitled “Digital Health: A Call for Government Leadership and Cooperation between ICT and Health” demonstrates the importance of ICT ministries and e-Government agencies joining forces with Ministries of Health to develop and implement national digital health strategies. A warm thank-you to the following speakers for having contributed to this important conversation: Hon. Aurelie Adam Soule Zoumarou (Minister of Digital Economy and Communication, Republic of Benin), Hon. Patrick Ndimubanzi (Minister of State, Ministry of Health, Rwanda), Houlin Zhao (Secretary General, International Telecommunications Union), Olu Olushayo Oluseun (World Health Organization- Country Representative) and Ann Aerts (Head of the Novartis Foundation). Here is a video to this session.

It was also such a pleasure to be a speaker on the panel focused on Digital Health for Universal Health Coverage and NCDs. More than 75% of NCD deaths - 31 million - occur in low- and middle-income countries and if you combine this with the shortage of health workers and health infrastructure in Africa, digital tools can make a significant contribution in tackling this rising crisis in Africa. This was a lively and passionate discussion which was moderated by Hani Eskandar (ICT Applications Coordinator ITU) with the following participants: Harald Nusser (Head of Novartis Social Business), Frasia Kura (General Manager at AMREF Health Africa), Prebo Barango (Medical Officer &Expert on NCDs at WHO Africa) and Dr. Sipula (CEO of Watifhealth, South Africa). Here is a video of the panel.

This is yet another conversation that serves as a prelude to a report on digital health and NCDs from the Digital Health Working Group from the Broadband Commission (co-chaired by the Novartis Foundation and Intel) which should be released in September around the UN High-Level Summit on NCDs in NY.

Sincere congratulations also to the African Alliance for Digital Health Networks for their official launch at Smart Africa

I will conclude by giving a special thanks to Jean-Philbert Nsengimana (who served until recently as ICT Minister in Rwanda and is now Special Advisor to Smart Africa) as he played a very important role in convincing stakeholders to make digital health a significant part of this impactful summit!

Here are videos of some of the other panels on digital health:

State of Digital Health in Africa

Investing in Digital Health: Business Models and PPPs

Innovation for Digital Health: Biotech, Drones, IoT, Mobile, Big Data, AI: Where Are the Quick Wins?

The recent 71st World Health Assembly was exciting for digital health champions like me!

First and foremost, the long-awaited and hoped-for Digital Health Resolution was approved urging Member States to prioritize the development and greater use of digital technologies in health as a means of promoting Universal Health Coverage and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. The resolution was proposed by Algeria, Australia, Brazil, Estonia, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Mauritius, Morocco, Panama, Philippines and South Africa. This move is significant and will hopefully mark another inflexion point in the development of digital health. India deserves special congratulations for having supported this initiative over the months.

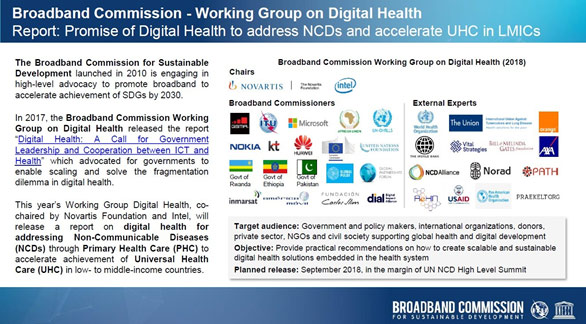

I was also thrilled at the high attendance and success of the event that I supported the NCD Alliance, the Novartis Foundation and Intel to organize which focused on the importance of digital health for addressing the challenge of NCDs. Although there were many events on NCDs at WHA last year, we had noted little mention was made of the significant potential digital health and technology could play in this space. Several players decided to act on this gap by raising awareness to the eco-system. This has spurred one of this year’s digital health working group from the Broadband Commission (co-chaired by the Novartis Foundation and Intel) to work on a global report which is due to be released in September around the UN High-Level Summit on NCDs in NY. Below is a snapshot of its content and its 36 working group members.

The event at WHA served in some ways as a prelude to this report and aimed to start raising awareness on this important subject. Health ministers and experts from Ghana, Rwanda and India discussed how governments and policies can make a difference in using the tool of digital health for NCDs and thereby improving UHC. WHO presented the important joint WHO-ITU “Be He@lthy, Be Mobile” initiative which has already achieved quite a bit assisting 9 countries to develop programs using mobile health targeting NCDs. The George Institute for Global Health, Siemens Healthineers, the NCD Alliance, the Novartis Foundation and Intel brought their insights on the importance of partnerships. The Carlos Slim Foundation spoke of their significant CASALUD NCD project which uses digital health and has reached over 12,000 health centers in Mexico and affected over 1,5 million patients.

The event was a great reminder of how powerful the tool of digital health can be in revolutionizing how NCDs care can be delivered by expanding access, improving efficiency and training less-skilled health workers. Of significant importance is the empowerment of patients managing their illness which is supported by connected devices, apps and digital solutions at large. Thanks a million to the NCD Alliance, Intel and the Novartis Foundation for the great teamwork. Stay tuned for the upcoming report from the digital health working group from the Broadband Commission!

Special congratulations also to the Commonwealth Centre for Digital Health for its recent launch and the wonderful event they also held at WHA. Several ministers of health were present, and the expertise shown in their speeches gave a glimpse of how the cycle of digital health is maturing and becoming more widespread in high-level political circles.

Here is also a good read from Ann Aerts, Head of the Novartis Foundation on WHA and digital health: Reflections on a great week at WHA71 as the World Health Assembly acknowledges digital health to fight NCDs and accelerate universal health coverage.

A national ICT framework that facilitates alignment between health and ICT sectors supported by effective governance mechanisms – and importantly, sustained senior government leadership and committed financing – are critical for the success of digital health at national levels.

Recounting experiences and associated developments particularly in the African context, Florence Gaudry-Perkins, founder and CEO of the Paris-based Digital Health Partnerships explained in her Africa Health Management Conference presentation at Gallagher Estate, Midrand, this week that by 2017, 23 African countries had already developed digital strategies for their healthcare delivery and management systems.

Digital health stumbling blocks commonly faced by countries at the outset include lack of common standards and appropriate legislation for digital health, insufficient human and technical capacity to collect and analyse health data, and lack of co-ordination between national ICT plans and national digital health strategies.

A notable exception in Africa, said Gaudry-Perkins, has been Rwanda with a personal interest and resulting co-operation at the highest level: “They have a very efficient system already up and running as a result. I come from France where some associates who have noticed Rwanda’s progress have gone so far as to suggest it be brought to the attention of the French government!”

A significant benefit achievable with the successful implementation of these technologies is the ability to reduce costs and increase efficiencies of healthcare systems: “Here they have the ability to use real-time data to make surveillance action-orientated and as such respond to health priorities.

“The promise of digital health also includes empowering patients to take more responsibility in the management of their own health, at the same time empowering providers with support systems.

“Importantly,” Gaudry-Perkins added, “it facilitates communication between providers, patients and communities.”

Health professionals are the cornerstone of any health system. Yet the world is facing a global shortage of health workers. A scarcity that - along with the global epidemic of non-communicable diseases - is one of the most critical obstacles to the achievement of the sustainable development goals. Shared solutions are needed that involve extensive changes in global health education and health practitioners’ training.

In developing countries, the health workforce crisis is even more concerning with only 0.2 doctors and 1.2 nurses or midwifes per 1,000 people in Sub-Saharan Africa.[1] In 2013, the WHO estimated a global shortage of over 17 million healthcare workers, mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia.[2]

The underlying problem is a lack of resources and a huge shortfall in educating health workers. In 2014, fifty per cent of all medical schools in the world were located in ten countries. In America, there is one medical school per 1.2 million people; whereas Africa has only one per 5 million.[3]

One of the key recommendations of the “Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world” report by the Lancet Commission is “exploiting the power of Information Technology (IT) for learning.”

With Africa, for example, reaching 80% of mobile penetration in 2016,[4] ICTs undeniably represent powerful tools in facilitating access to health workers’ education.

One of the main benefits of digital training is that boundaries do not limit access or participation. A teacher in Kenya can teach the same material in any English-language school. This is why institutions can increase the number of course offerings and the number of students or teachers reached thanks to video and audio streaming of lectures, mobile-based multiple-choice questionnaires, or Q&A for distance training. Open-source learning materials and social networking learning approaches are thus becoming the basis of mobile education.

These mobile tools can be used also for short-term training such as when facing an emergency. To face an epidemic, health professionals must know how to act appropriately.During Ebola, Liberia’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare partnered with UNICEF and Intrahealth International to provide health workers with online materials that demonstrated the correct practices to avoid infection.[5]

But implementing long-term training programsthat provide health practitioners with consistent and replicable education is most important. The Indian government has recently launched a nationwide mHealth program that aims to train one million community health professionals to reach 10 million pregnant women. As of today, 258,241 of these community health workers have started this training course in nine states, and 147,177 have already graduated.[6]

Amref in Africa is another organization well versed in using ICTs for medical training as they have trained to date 20,000 nurses in Africa using eLearning. Over the last four years, Amref Health Africa has developed a mobile learning solution in partnership with the Ministry of Health, M-Pesa Foundation, Accenture, and Safaricom and used mLearning to educate over 3,000 community health volunteers, thus providing over 300,000 community members with much-needed health education and basic health services.[7]

Training and educational digital-health approaches have the potential to empower health workers in remote areas, improve quality of care at the frontline, and reinforce health systems, as well as alleviate the workload at overburdened health facilities.

[1] “World Development Indicators: Health systems”, World Bank, 2017 (link).

[2] World Health Organization, Atlas of eHealth Country Profiles 2015 (link).

[3] Duvivier RJ, Boulet JR, Opalek A, Van Zanten M, Norcini J, 2014, “Overview of the world's medical schools: an update” (link).

[4] GSMA Intelligence, 2016.

[5] O’Donovan James, Bersin Amalia, “Controlling Ebola through mHealth strategies”, The Lancet, January 2015, Volume 3, No.1, e22.

[6] “BBC Media Centre, Government of India and BBC Media Action Launch Free Mobile Health Education to Millions of Women”, 2016.

[7] Link.

The world was caught unprepared when Ebola struck West Africa in late 2013. The aftermath: over 30,000 Ebola cases, including more than 11,000 dead, and billions of lost dollars. The Ebola crisis showed us the critical importance of strong health information systems, including the use of digital information and communication technologies (ICTs), to enable resilience to disease outbreaks.

USAID has recently published a remarkable report that demonstrates the role of digital health in responding to viral diseases as fatal as Ebola: Fighting Ebola with Information: Learning from the Use of Data, Information, and Digital Technologies in the Ebola Outbreak Response. The report discusses how data collection and analysis was critical to stopping the spread of disease, and for communities how digital communication tools (as simple as an SMS) were used to provide the population with much-needed information. To contain Ebola, national and international actors needed precise and timely data to provide effective relief. Yet the response initially struggled to fully leverage the power of digital technology to rapidly gather, transmit, analyze and share Ebola-related data in large part because technical, institutional, and workforce capacity were not robust enough.

Releasing the full benefit of digital technologies requires investing in human capacity, institutional policies and procedures, as well as the physical infrastructure that extends digital connectivity. Along with these structural changes, “quick wins” can be considered. Recommendations of the report suggest - among others - the more consistent use of machine-readable forms, the use of digital data collection tools with the ability to capture data in both online and offline environments, and performing rapid communications assessments after emergencies to understand and address gaps in access to digital communications.

Among the challenges cited in the report is the lack of standards and interoperability, a topic of the recently released digital health report from the Broadband Commission working group “Digital Health: A call for Government Leadership and Cooperation between ICT and Health”, and data silos, whereby information is not recognized from one system to the next, contributed to unclear and asynchronous information in the Ebola outbreak, complicating the response. Government leaders have a significant role to play in setting standards to solve part of this fragmentation, as do the international donors who historically have funded competing and non-interoperable data systems. We see one path toward enabling greater harmonization of digital health investments in a recent initiative discussed by the heads of USAID’s global health bureau and development lab in this blog: Digital Health: Moving from Silos to Systems.

I just recently attended Mobile World Congress (attended by 100 000 people this year) where I am happy to say we released an important report for accelerating digital health: “Digital Health: A call for Government Leadership and Cooperation between ICT and Health”.

I was involved in this work from its inception all the way to contributing this fall to its writing and I am feeling very grateful to the Novartis Foundation and also Nokia for having co-chaired and supported what turned out to be a major collaborative effort with key actors and policymakers of the global digital health ecosystem. One of the reasons I believe this report will have an impact is that it is being released by the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development which is a highly influential body established in 2010 comprised of more than 50 leaders from across a range of government and industry sectors.

In brief, as the cycle of digital health evolves, there is a growing realization of the fundamental role governments have to play in advancing the use of technology for health. Fragmentation, data interoperability and lack of appropriate legislation and laws are still prevalent, and many of these challenges will not be overcome without stronger government leadership and improved cooperation and coordination between health and ICT authorities (typically ministries of Communication and eGovernment agencies). To give you a striking example of what we mean by fragmentation; there are eleven different mobile health initiatives for maternal and child health funded by different institutions in Mali. Most of these institutions use their own tools and systems which are not interoperable with the current systems used by the national eHealth agency.

For anyone interested in scaling digital health, I therefore highly recommend the read of this report: “Digital Health: A call for Government Leadership and Cooperation between ICT and Health”. Beyond its key recommendations, the report developed case studies in 8 countries that managed to effectively advance the digital health agenda. Those countries are: Canada, Estonia, Malaysia, Mali, Nigeria, Norway, the Philippines and Rwanda. They all provide key insights and lessons which other countries can leverage from. Although not many countries have yet analyzed the impact of digital health on their systems, it is notable for other governments to see that Canada recently estimated that their investments in digital health generated savings of $15 billion since 2007. ITU and WHO established a very comprehensive National eHealth Strategy Toolkit back in 2012 which many governments have already used around the world. Let’s hope this report will do both: motivate countries that have not yet developed such strategies, and support those countries that already developed their strategies and are moving towards the complex task of implementation.